Transcription of A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview

1 212 THEORY INTO PRACTICE / Autumn 2002 Revising bloom s TaxonomyDavid R. Krathwohl is Hannah Hammond Professor ofEducation Emeritus at Syracuse taxonomy OF EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES is a framework for classifying statements ofwhat we expect or intend students to learn as aresult of instruction. The framework was conceivedas a means of facilitating the exchange of test itemsamong faculty at various universities in order tocreate banks of items, each measuring the sameeducational objective. Benjamin S. bloom , thenAssociate Director of the Board of Examinations ofthe University of Chicago, initiated the idea, hopingthat it would reduce the labor of preparing annualcomprehensive examinations. To aid in his effort, heenlisted a group of measurement specialists fromacross the United States, many of whom repeatedlyfaced the same problem.

2 This group met about twicea year beginning in 1949 to consider progress, makerevisions, and plan the next steps. Their final draftwas published in 1956 under the title, taxonomy ofEducational Objectives: The Classification of Edu-cational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain( bloom , Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956).1 Hereafter, this is referred to as the original Taxono-my. The Revision of this framework, which is thesubject of this issue of Theory Into Practice, wasdeveloped in much the same manner 45 years later(Anderson, Krathwohl, et al., 2001). Hereafter, thisis referred to as the revised saw the original taxonomy as more thana measurement tool. He believed it could serve as a common language about learning goals to facili-tate communication across persons, subject matter,and grade levels; basis for determining for a particular course orcurriculum the specific meaning of broad educa-tional goals, such as those found in the currentlyprevalent national, state, and local standards; means for determining the congruence of educa-tional objectives, activities, and assessments ina unit, course, or curriculum; and panorama of the range of educational possibili-ties against which the limited breadth and depthof any particular educational course or curricu-lum could be Original TaxonomyThe original taxonomy provided carefullydeveloped definitions for each of the six major cat-egories in the cognitive domain.

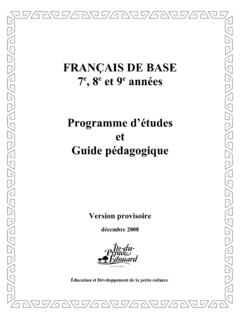

3 The categorieswere Knowledge, Comprehension, Application,Analysis, Synthesis, and With the ex-ception of Application, each of these was brokeninto subcategories. The complete structure of theoriginal taxonomy is shown in Table categories were ordered from simple tocomplex and from concrete to abstract. Further, itwas assumed that the original taxonomy repre-sented a cumulative hierarchy; that is, mastery ofTHEORY INTO PRACTICE, Volume 41, Number 4, Autumn 2002 Copyright 2002 College of Education, The Ohio State UniversityDavid R. KrathwohlA Revision of bloom s Taxonomy: An Overview 213An OverviewKrathwohleach simpler category was prerequisite to masteryof the next more complex the time it was introduced, the term tax-onomy was unfamiliar as an education term.

4 Po-tential users did not understand what it meant,therefore, little attention was given to the originalTaxonomy at first. But as readers saw its poten-tial, the framework became widely known and cit-ed, eventually being translated into 22 of the most frequent uses of the originalTaxonomy has been to classify curricular objec-tives and test items in order to show the breadth,or lack of breadth, of the objectives and itemsacross the spectrum of categories. Almost always,these analyses have shown a heavy emphasis onobjectives requiring only recognition or recall ofinformation, objectives that fall in the Knowledgecategory. But, it is objectives that involve the under-standing and use of knowledge, those that would beclassified in the categories from Comprehension toSynthesis, that are usually considered the most im-portant goals of education.

5 Such analyses, therefore,have repeatedly provided a basis for moving curricu-la and tests toward objectives that would be classi-fied in the more complex One Dimension to Two DimensionsObjectives that describe intended learningoutcomes as the result of instruction are usuallyframed in terms of (a) some subject matter contentand (b) a description of what is to be done with or tothat content. Thus, statements of objectives typicallyconsist of a noun or noun phrase the subject mattercontent and a verb or verb phrase the cognitiveprocess(es). Consider, for example, the followingobjective: The student shall be able to rememberthe law of supply and demand in economics. Thestudent shall be able to (or The learner will, orsome other similar phrase) is common to all objec-tives since an objective defines what students areexpected to learn.

6 Statements of objectives oftenomit The student shall be able to phrase, speci-fying just the unique part ( , Remember theeconomics law of supply and demand. ). In thisform it is clear that the noun phrase is law ofsupply and demand and the verb is remember. In the original taxonomy , the Knowledge cate-gory embodied both noun and verb aspects. The nounor subject matter aspect was specified in Knowledge sextensive subcategories. The verb aspect was includ-ed in the definition given to Knowledge in that thestudent was expected to be able to recall or recog-nize knowledge. This brought unidimensionality tothe framework at the cost of a Knowledge categorythat was dual in nature and thus different from theother Taxonomic categories. This anomaly was elim-inated in the revised taxonomy by allowing thesetwo aspects, the noun and verb, to form separate di-mensions, the noun providing the basis for the Knowl-edge dimension and the verb forming the basis forthe Cognitive Process 1 Structure of the Original taxonomy Knowledge of Knowledge of Knowledge of specific Knowledge of ways and means of dealing Knowledge of Knowledge of trends and Knowledge of classifications and Knowledge of Knowledge of Knowledge of universals and abstractions in Knowledge of principles and Knowledge of theories and structures Extrapolation Application Analysis of Analysis of Analysis of organizational principles Production of a unique Production of a plan.

7 Or proposed set of Derivation of a set of abstract relations Evaluation in terms of internal Judgments in terms of external criteria214 THEORY INTO PRACTICE / Autumn 2002 Revising bloom s TaxonomyThe Knowledge dimensionLike the original, the knowledge categoriesof the revised taxonomy cut across subject matterlines. The new Knowledge dimension, however,contains four instead of three main of them include the substance of the subcat-egories of Knowledge in the original they were reorganized to use the terminology,and to recognize the distinctions of cognitive psy-chology that developed since the original frame-work was devised. A fourth, and new category,Metacognitive Knowledge, provides a distinctionthat was not widely recognized at the time the orig-inal scheme was developed.

8 Metacognitive Knowl-edge involves knowledge about cognition in generalas well as awareness of and knowledge about one sown cognition (Pintrich, this issue). It is of in-creasing significance as researchers continue todemonstrate the importance of students being madeaware of their metacognitive activity, and then us-ing this knowledge to appropriately adapt the waysin which they think and operate. The four catego-ries with their subcategories are shown in Table Cognitive Process dimensionThe original number of categories, six, was re-tained, but with important changes. Three categorieswere renamed, the order of two was interchanged,and those category names retained were changed toverb form to fit the way they are used in verb aspect of the original Knowledgecategory was kept as the first of the six major cat-egories, but was renamed Remember.

9 Comprehen-sion was renamed because one criterion forselecting category labels was the use of terms thatteachers use in talking about their work. Becauseunderstand is a commonly used term in objectives,its lack of inclusion was a frequent criticism of theoriginal taxonomy . Indeed, the original group con-sidered using it, but dropped the idea after furtherconsideration showed that when teachers say theywant the student to really understand, they meananything from Comprehension to Synthesis. But,to the revising authors there seemed to be popularusage in which understand was a widespread syn-onym for comprehending. So, Comprehension, thesecond of the original categories, was 2 Structure of the Knowledge Dimensionof the Revised taxonomy A. Factual Knowledge The basic elements that stu-dents must know to be acquainted with a disciplineor solve problems in Knowledge of terminologyAb.

10 Knowledge of specific details and elements B. Conceptual Knowledge The interrelationshipsamong the basic elements within a larger structurethat enable them to function Knowledge of classifications and categoriesBb. Knowledge of principles and generalizationsBc. Knowledge of theories, models, and structures C. Procedural Knowledge How to do something; meth-ods of inquiry, and criteria for using skills, algorithms,techniques, and Knowledge of subject-specific skills and al-gorithmsCb. Knowledge of subject-specific techniques andmethodsCc. Knowledge of criteria for determining whento use appropriate procedures D. Metacognitive Knowledge Knowledge of cognitionin general as well as awareness and knowledge ofone s own Strategic knowledgeDb. Knowledge about cognitive tasks, includingappropriate contextual and conditionalknowledgeDc.