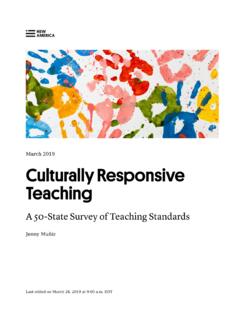

Transcription of PREPARING FOR CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING

1 Journal of Teacher Education, Vol. 53, No. 2, March/April 2002. 2001 AACTE OUTSTANDING WRITING AWARD RECIPIENT. Editor's Note: This article draws from geneva Gay's recent book, CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING : Theory, Research, and Practice, which received the 2001 Outstanding Writing Award from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. PREPARING FOR CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING . geneva Gay University of Washington, Seattle In this article, a case is made for improving the them more effectively. It is based on the assump- school success of ethnically diverse students tion that when academic knowledge and skills through CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING and for are situated within the lived experiences and PREPARING teachers in preservice education pro- frames of reference of students, they are more grams with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills personally meaningful, have higher interest ap- needed to do this.

2 The ideas presented here are peal, and are learned more easily and thoroughly brief sketches of more thorough explanations (Gay, 2000). As a result, the academic achieve- included in my recent book, CULTURALLY Respon- ment of ethnically diverse students will improve sive TEACHING : Theory, Research, and Practice (2000). when they are taught through their own cul- The specific components of this approach to tural and experiential filters (Au & Kawakami, TEACHING are based on research findings, theo- 1994; Foster, 1995; Gay, 2000; Hollins, 1996;. retical claims, practical experiences, and per- Kleinfeld, 1975; Ladson-Billings, 1994, 1995). sonal stories of educators researching and work- ing with underachieving African, Asian, Latino, DEVELOPING A CULTURAL. and Native American students. These data were DIVERSITY KNOWLEDGE BASE. produced by individuals from a wide variety of disciplinary backgrounds including anthropol- Educators generally agree that effective teach- ogy, sociology, psychology, sociolinguistics, com- ing requires mastery of content knowledge and munications, multicultural education, K-college pedagogical skills.

3 As Howard (1999) so aptly classroom TEACHING , and teacher education. Five stated, We can't teach what we don't know.. essential elements of CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE teach- This statement applies to knowledge both of ing are examined: developing a knowledge base student populations and subject matter. Yet, too about cultural diversity, including ethnic and many teachers are inadequately prepared to teach cultural diversity content in the curriculum, dem- ethnically diverse students. Some professional onstrating caring and building learning com- programs still equivocate about including multi- munities, communicating with ethnically diverse cultural education despite the growing num- students, and responding to ethnic diversity in bers of and disproportionately poor performance the delivery of instruction. CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE of students of color. Other programs are trying TEACHING is defined as using the cultural charac- to decide what is the most appropriate place and teristics, experiences, and perspectives of ethni- face for it.

4 A few are embracing multicultural cally diverse students as conduits for TEACHING education enthusiastically. The equivocation is Journal of Teacher Education, Vol. 53, No. 2, March/April 2002 106-116. 2002 by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education 106. inconsistent with PREPARING for CULTURALLY respon- ence) and cultural diversity are incompatible, or sive TEACHING , which argues that explicit knowl- that combining them is too much of a concep- edge about cultural diversity is imperative to tual and substantive stretch for their subjects to meeting the educational needs of ethnically diverse maintain disciplinary integrity. This is simply students. not true. There is a place for cultural diversity in Part of this knowledge includes understand- every subject taught in schools. Furthermore, ing the cultural characteristics and contribu- CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING deals as much tions of different ethnic groups (Hollins, King, & with using multicultural instructional strate- Hayman, 1994; King, Hollins, & Hayman, 1997; gies as with adding multicultural content to the Pai, 1990; Smith, 1998).

5 Culture encompasses curriculum. Misconceptions like these stem, in many things, some of which are more important part, from the fact that many teachers do not for teachers to know than others because they know enough about the contributions that dif- have direct implications for TEACHING and learn- ferent ethnic groups have made to their subject ing. Among these are ethnic groups' cultural areas and are unfamiliar with multicultural edu- values, traditions, communication, learning styles, cation. They may be familiar with the achieve- contributions, and relational patterns. For exam- ments of select, high-profile individuals from ple, teachers need to know (a) which ethnic some ethnic groups in some areas, such as Afri- groups give priority to communal living and can American musicians in popular culture or cooperative problem solving and how these pref- politicians in city, state, and national govern- erences affect educational motivation, aspira- ment.

6 Teachers may know little or nothing about tion, and task performance; (b) how different the contributions of Native Americans and Asian ethnic groups' protocols of appropriate ways Americans in the same arenas. Nor do they for children to interact with adults are exhibited know enough about the less publicly visible but in instructional settings; and (c) the implications very significant contributions of ethnic groups of gender role socialization in different ethnic in science, technology, medicine, math, theol- groups for implementing equity initiatives in ogy, ecology, peace, law, and economics. classroom instruction. This information consti- Many teachers also are hard-pressed to have tutes the first essential component of the knowl- an informed conversation about leading multi- edge base of CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING . Some cultural education scholars and their major pre- of the cultural characteristics and contributions mises, principles, and proposals.

7 What they think of ethnic groups that teachers need to know are they know about the field is often based on explained in greater detail by Gold, Grant, and superficial or distorted information conveyed Rivlin (1977); Shade (1989); Takaki (1993); Banks through popular culture, mass media, and crit- and Banks (1995); and Spring (1995). ics. Or their knowledge reflects cursory aca- The knowledge that teachers need to have demic introductions that provide insufficient about cultural diversity goes beyond mere aware- depth of analysis of multicultural education. ness of, respect for, and general recognition of These inadequacies can be corrected by teach- the fact that ethnic groups have different values ers' acquiring more knowledge about the con- or express similar values in various ways. Thus, tributions of different ethnic groups to a wide the second requirement for developing a knowl- variety of disciplines and a deeper understand- edge base for CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING is ing of multicultural education theory, research, acquiring detailed factual information about the and scholarship.

8 This is a third important pillar cultural particularities of specific ethnic groups of the knowledge foundation of CULTURALLY respon- ( , African, Asian, Latino, and Native Ameri- sive TEACHING . Acquiring this knowledge is not can). This is needed to make schooling more as difficult as it might at first appear. Ethnic interesting and stimulating for, representative individuals and groups have been making wor- of, and RESPONSIVE to ethnically diverse students. thy contributions to the full range of life and cul- Too many teachers and teacher educators think ture in the United States and humankind from that their subjects (particularly math and sci- the very beginning. And there is no shortage of Journal of Teacher Education, Vol. 53, No. 2, March/April 2002 107. quality information available about multicul- decontextualizing women, their issues, and their tural education. It just has to be located, learned, actions from their race and ethnicity; ignoring and woven into the preparation programs of poverty; and emphasizing factual information teachers and classroom instruction.)

9 This can be while minimizing other kinds of knowledge (such accomplished, in part, by all prospective teach- as values, attitudes, feelings, experiences, and ers taking courses on the contributions of ethnic ethics). CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING reverses groups to the content areas that they will teach these trends by dealing directly with contro- and on multicultural education. versy; studying a wide range of ethnic individu- als and groups; contextualizing issues within DESIGNING CULTURALLY race, class, ethnicity, and gender; and including RELEVANT CURRICULA multiple kinds of knowledge and perspectives. It also recognizes that these broad-based analy- In addition to acquiring a knowledge base ses are necessary to do instructional justice to about ethnic and cultural diversity, teachers need the complexity, vitality, and potentiality of eth- to learn how to convert it into CULTURALLY respon- nic and cultural diversity.

10 One specific way to sive curriculum designs and instructional strat- begin this curriculum transformation process is egies. Three kinds of curricula are routinely to teach preservice (and inservice) teachers how present in the classroom, each of which offers to do deep cultural analyses of textbooks and different opportunities for TEACHING cultural other instructional materials, revise them for diversity. The first is formal plans for instruction better representations of CULTURALLY diversity, and approved by the policy and governing bodies of provide many opportunities to practice these educational systems. They are usually anchored skills under guided supervision. Teachers need in and complemented by adopted textbooks to thoroughly understand existing obstacles to and other curriculum guidelines such as the CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE TEACHING before they can standards issued by national commissions, successfully remove them.