Transcription of Preventing Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism

1 Preventing Hospital-Associated Venous ThromboembolismA Guide for Effective Quality Improvement Preventing Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism A Guide for Effective Quality Improvement Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 Prepared by: Greg Maynard , , SFHM University of California, San Diego Medical Center Department of Medicine, Division of hospital Medicine Director, UCSD Center for Innovation and Improvement Science AHRQ Publication No. 16-0001-EF Replaces AHRQ Publication No. 08-0075 Updated August 2016 ii The author discloses that he has acted as an expert in cases involving Venous Thromboembolism (VTE). Dr. Maynard also sits on an expert review panel for a phase 3 study on rivaroxaban for VTE prophylaxis in medical patients (Mariner study, Janssen Pharmaceuticals). He has no other affiliations or financial involvement ( , employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock options, grants, patents received or pending, or royalties) that conflict with material presented in this guide.

2 This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission. Citation of the source is appreciated. Suggested Citation Maynard G. Preventing Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism : a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2016. AHRQ Publication No. 16-0001-EF. iii Acknowledgments The author would like to acknowledge those who contributed to the first version of the guide, most notably Dr. Jason Stein of Emory University. Dr. Maynard has also been inspired by all those who have engaged in collaborative improvement efforts using the previous version of this guide; these have greatly informed this updated and revised version. In addition, many individuals contributed a great deal of their time and expertise to the development of the revised guide. For their expert input, the author gratefully acknowledges the following individuals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Michele G.

3 Beckman, , Epidemiologist, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; Scott Grosse, , Research Economist, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; and Lisa C. Richardson, , , Director of Division of Cancer Prevention and Control From the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety at AHRQ: Barbara Bartman, , , Medical Officer and AHRQ VTE clinical expert advisor; Jeff Brady, , , Rear Admiral, Public Health Service and Director, CQuIPS; Eileen M. Hogan, , Public Health Analyst. Finally, AHRQ and the author acknowledge the patients and families who have shared their personal stories about the impact VTE had on their lives and their insights into the importance of prevention efforts. Peer Reviewers Before publication of the revised guide, AHRQ sought input from independent peer reviewers without financial conflicts of interest. Please note that the conclusions and information presented in this guide do not necessarily represent the views of individual reviewers.

4 The list of peer reviewers follows: Alpesh N. Amin, Chair, Department of Medicine; School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA David Garcia, Professor, University of Washington School of Medicine, University of Washington Seattle, WA iv William Geerts, Affiliate Scientist, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Toronto, ON Elliott Richard Haut, , Fellowship Director, Trauma/Acute Care Surgery Fellowship and Associate Professor of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins hospital Baltimore, MD Michael Gould, , Director for Health Services Research and Implementation Science, Kaiser Permanente Southern California Pasadena, CA Gary E. Raskob, Dean and Regents Professor, College of Public Health, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Oklahoma City, OK Michael Streiff, Medical Director, Anticoagulation Management Service and Outpatient Clinics and Associate Professor of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins hospital Baltimore, MD Richard H.

5 White, Chief of General Medicine and Professor of Medicine, University of California, Davis Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, Lawrence J. Ellison Ambulatory Care Center, General Medicine Sacramento, CA Neil A. Zakai, , Associate Professor of Medicine, Hematology/Oncology Division, Department of Medicine and Associate Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine University of Vermont College of Medicine, Colchester Research Facility Colchester, VT v Table of Contents vii Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism as a Public Health Problem .. vii Purpose of This Guide .. viii What s New in This Guide .. ix How To Use the Guide and Related Tools and Resources ..x Executive Summary ..1 Chapter 1. The Framework for Improvement ..3 Essential First Steps ..4 Stages of the Quality Improvement Effort ..10 Chapter 2. Analyze Care Delivery ..12 Identify Common Barriers to Improvement ..12 Identify Common Failure Modes ..13 Diagram Care Delivery To Identify Failure Modes.

6 14 Chapter 3. Outline the Evidence and Identify Best Practices ..16 Know What the Literature Says About the Risk of Venous Thromboembolisms and Measures for Prevention ..16 Putting It All Together Next Steps ..21 Chapter 4. Choose the Model To Assess VTE and Bleeding Risk ..23 Overview Major Categories and Characteristics of VTE Risk Assessment Models ..24 Chapter 5. Implement the VTE Prevention Protocol ..35 The Importance of Effective Implementation ..35 Five Principles for Effective Implementation in Clinical Decision Support ..36 Chapter 6. Track Performance with Metrics ..41 The Importance and Purpose of Categories of Metric Selection ..44 Summary of the Approach to Measurement ..56 Chapter 7. Layering Interventions and Moving Toward Excellence ..57 Reviewing the Basics Order Set Design and Implementation ..57 Beyond the Basics Addressing Failure Modes and Layering Interventions ..57 Achieving Measure-vention: Reaching Level 5 on the Hierarchy of Taking Measure-vention to the Next Level.

7 66 Chapter 8. Continue To Improve, Hold the Gains, and Spread the Results ..67 Maintain and Spread the Gains ..68 References ..69 Preface ..69 Chapter 1 ..72 Chapter 2 ..73 Chapter 3 ..73 Chapter 4 ..74 Chapter 5 ..76 Chapter 6 ..77 Chapter 7 ..78 vi Figures Figure : Framework for Improving VTE Prevention ..3 Figure : Process Map of VTE Prophylaxis With Common Areas of Failure ..15 Figure : DVT Prophylaxis Orders ..24 Figure : Classic 3 Bucket Model Derived From AT8 ..26 Figure : Updated 3 Bucket Model In Use at UC San Diego ..27 Figure : Scoring and Recommended Prophylaxis .. Error! Bookmark not defined. Figure : Padua Risk Assessment Model for Nonsurgical InpatientsError! Bookmark not defined. Figure : IMPROVE VTE Risk Model 4 Factor Version (Risk Factors Available on Admission) .. Error! Bookmark not defined. Figure : IMPROVE VTE Risk Model 7 Factor Version (Includes Risk Factors That May Develop During the hospital Stay).

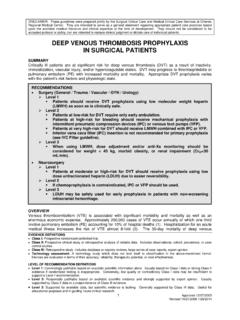

8 Error! Bookmark not defined. Figure : Outcomes Chain for HA-VTE ..43 Figure : Automated Version of a Stoplight Report ..49 Figure : Comparison of Tabular Data and Run Chart on Appropriate Prophylaxis (from UC San Diego Medical Center) ..54 Figure : Run Chart of Prophylaxis Patterns ..55 Figure : SPC Chart of the Percentage of Patients With Adequate Prophylaxis ..56 Figure : Percentage of Ordered Subcutaneous Pharmacologic Prophylaxis Doses That Were Not Administered to Adult Inpatients ..61 Figure : Excerpt From Automated Measure-vention Screening Tool (Enhanced Stoplight Method) ..65 Tables Table : Hierarchy of Reliability ..11 Table : Major Guidelines Addressing VTE Prophylaxis ..16 Table : Characteristics of Four Empirically Derived Models for VTE Risk ..32 Table : Bleeding Risk Factors and Conditions To Consider With Pharmacologic VTE Prophylaxis ..34 Table : National hospital Inpatient Quality Measures for VTE Prevention and Management 44 Table : Common Failure Modes in Providing Optimal VTE Prophylaxis and Strategies and Solutions To Address Them.

9 58 Table : Advantages of Plan-Do-Study-Act and Principles for Success ..67 vii Preface Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism as a Public Health Problem Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), collectively known as Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), represent a major public health problem that affects 350,000 to 600,000 Americans Estimates vary widely, but the overall annual prevalence may be VTE is primarily a problem of sick or injured patients who are hospitalized or were recently hospitalized,3,4 and it is frequently estimated to be among the most common preventable causes of hospital Symptomatic DVT and PE are associated with extended duration of inpatient stays and high (10-15 percent) fatality rates. VTE generally requires therapeutic anticoagulation for a minimum of 3 ,9 This therapeutic anticoagulation is associated with 1 to 2 percent major bleeding per patient year, resulting in fatal bleeding at least to percent per patient year in clinical trials.

10 In real-world practices, the rates are much When patients survive the VTE event and acute course of anticoagulant therapy and all the inconvenience, anxiety, and cost that represents they are still at risk for other complications. More than 20 percent of patients with proximal DVT/PE will suffer a recurrent event once anticoagulation has been discontinued, along with all the readmissions, mortality, and morbidity risk that Furthermore, 30 to 50 percent of DVT patients will develop postthrombotic syndrome,14 and an estimated 4 percent of PE patients will develop chronic thromboembolic pulmonary Patients and their families relay powerful personal stories related to loss of function, difficulty with anticoagulant therapy, fiscal burden, and fear of recurrence. Thromboprophylaxis for at-risk inpatients can reduce VTE by 30 to 65 percent, has a low incidence of major bleeding complications, and has well-documented ,17 Numerous guidelines from authoritative bodies outlining appropriate use of thromboprophylaxis are available,16,18-24 yet study after study reflects unacceptably low rates of thromboprophylaxis in patients at For example, a recent cross-sectional international study of almost 70,000 patients in 358 hospitals found that appropriate prophylaxis was administered in only percent of surgical and percent of medical inpatients at risk for VTE27; another registry found only 42 percent of patients with Hospital-Associated DVT received prophylaxis within 30 days prior to This constellation of facts presents a powerful imperative for improvement.