Transcription of The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation ...

1 The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation :a systematic review of the literatureAndreas Stefan Rothgangela,f, Susy M. Brauna,b,c,d, Anna J. Beurskensa,b,c,Ru diger J. Seitzgand Derick T. Wadee,hThe objective of this study was to evaluate the clinicalaspects of mirror therapy (MT) interventions after stroke,phantom limb pain and complex regional pain systematic literature search of the Cochrane Database ofcontrolled trials, PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE,PsycINFO, PEDro, RehabTrials and Rehadat, was made bytwo investigators independently ( and ). Norestrictions were made regarding study design and type orlocalization of stroke, complex regional pain syndrome andamputation. Only studies that had MT given as a long-termtreatment were included. Two authors ( and )independently assessed studies for eligibility and risk ofbias by using the Amsterdam Maastricht Consensus randomized trials, seven patient series and foursingle-case studies were included. The studies wereheterogeneous regarding design, size, conditions studiedand outcome measures.

2 Methodological quality varied; onlya few studies were of high quality. Important clinicalaspects, such as assessment of possible side effects, wereonly insufficiently addressed. For stroke there is amoderate quality of evidence that MT as an additionalintervention improves recovery of arm function, and a lowquality of evidence regarding lower limb function and painafter stroke. The quality of evidence in patients withcomplex regional pain syndrome and phantom limb pain isalso low. Firm conclusions could not be drawn. Little isknown about which patients are likely to benefit most fromMT, and how MT should preferably be applied. Futurestudies with clear descriptions of intervention protocolsshould focus on standardized outcome measures andsystematically register adverse of rehabilitation Research34:1 13 c2011 WoltersKluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Journal of rehabilitation Research2011,34:1 13 Keywords: feedback, imagery (psychotherapy), mirror , physical therapy , rehabilitation , reviewaThe Department of Health and Technique, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences,bThe Centre of Expertise in Life Sciences,cThe Research Centre Autonomyand Participation for People with Chronic Illnesses, Zuyd University, Heerlen,dThe Care and Public Health Institute,eDepartment of rehabilitation , MaastrichtUniversity, Maastricht, The Netherlands,fDepartment of Pain Management,Berufsgenossenschaftliches Universita tsklinikum Bergmannsheil GmbH Bochum,Ruhr-University, Bochum,gDepartment of Neurology, Duesseldorf UniversityHospital, Duesseldorf, Germany andhOxford Centre for Enablement, Oxford, UKCorrespondence to Andreas Stefan Rothgangel, , Department of Healthand Technique, Zuyd University, Nieuw Eyckholt 300, 6419 DJ Heerlen,The NetherlandsTel: +31 45 4006371; fax: +31 45 4006369.

3 E-mail: November 2010 Accepted27 December 2010 IntroductionIn mirror therapy (MT), the patient sits in front of a mirrorthat is oriented parallel to his midline blocking the view ofthe (affected) limb, positioned behind the mirror . Whenlooking into the mirror , the patient sees the reflection ofthe unaffected limb positioned as the affected limb. Thisarrangement is suited to create a visual illusion wherebymovement of or touch to the intact limb may be perceivedas affecting the paretic or painful limb. MT has beenused to treat patients suffering from stroke (Altschuleret al., 1999; Yavuzeret al.,2008;Dohleet al., 2009; Cacchioet al., 2009b), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)(McCabeet al., 2003; Moseley, 2004) and other pain syn-dromes such as peripheral nerve injury and following surgicalinterventions (Rosen and Lundborg, 2005; Gruenert-Pluesset al., 2008). Three particular conditions that have beenstudied the most are stroke, CRPS and phantom limb pain(PLP) (Ezendamet al.,2009).

4 The underlying mechanisms of the effects in these threepatient groups have mainly been related to the activationof mirror neurones , which may also be activated whenobserving others perform movements and also duringmental practice of motor tasks (Buccinoet al.,2006;Filimonet al., 2007). mirror neurons were found in areas ofthe ventral and inferior premotor cortex associated withobservation and imitation of movements and in somato-sensory cortices associated with observation of touch (DiPellegrinoet al., 1992; Rizzolattiet al.,1996;Keyserset al.,2004). These cortical areas are supposed to be activated byMT (Stevens and Stoykov, 2003; Matthyset al., 2009).Until now, direct evidence for the mirror -related recruit-ment of mirror neurons is lacking (Matthyset al.,2009;Dierset al., 2010; Michielsenet al., 2010). Other potentialmechanisms such as enhanced self-awareness and spatialattention by activation of the superior temporal gyrus,precuneus and the posterior cingulate cortex have beenproposed (Rothgangelet al.)

5 , 2006; Matthyset al.,2009;Michielsenet al., 2010). The superior temporal gyrus is alsothought to play an important role in recovery from neglect(Karnath, 2001; Karnathet al., 2001), and is activated byobservation of biological motion (Allisonet al.,2000).Review article 10342-5282 c2011 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & WilkinsDOI: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is three reviews on the topic of MT have beenpublished (Ezendamet al., 2009; Ramachandran andAltschuler, 2009; Seidelet al., 2009), concentrating on theeffectiveness of MT in different diseases. In contrast tothese studies, our study focuses on the clinical aspects ofMT interventions, which have not yet explicitly beenaddressed and in addition includes recently publishedpapers. In addition, our study includes only those studiesthat had MT given as a long-term treatment, defined asmore than two interventions. We defined clinical aspects of MT interventions as a compound of clinically relevantfactors that allow for reproduction of the interventionin daily practice.

6 These include detailed informationon treatment and patient characteristics, use of clinicallyrelevant outcome measures and description of possibleside effects of the , the main objective of this study was to conduct asystematic review on the clinical aspects of applying MTinterventions after stroke, PLP and CRPS (Fig. 1).Materials and methodsCriteria for considering studies for this reviewTypes of studiesThe studies included in this review were all availablearticles published before August 2010 in English, German,French and Dutch. All randomized controlled trials(RCTs), nonrandomized controlled clinical trials (CCTs)and other studies ( single-case studies or case series)evaluating the clinical aspects of MT were articles were categorized according to their studydesign (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2009):(1) Class I: randomized controlled studies;(2) Class II: cohort studies and nonrandomized CCTs;(3) Class III: case control studies;(4) Class IV: single-case studies and patient of participantsAll studies that involved adult patients (aged > 18 years)suffering from stroke, PLP or CRPS were included.

7 Norestrictions were made with regard to the type or localizationof stroke, CRPS and of interventionsTo be included, studies had to have MT given as a long-term treatment, defined as more than two interventions,either as the only therapy intervention or in combinationwith other types of treatment strategies. Studies thatincluded only one or two MT treatments to determineimmediate effects were the purpose of this study, MT was defined as theuse of a mirror reflection of unaffected limb movementssuperimposed on the affected extremity. Therefore, studiescould use a parasagittal mirror or a modified mirror device(451) suggesting movements made by the affected illusory mechanisms such as using immersive virtualreality were of outcome measuresAccording to the aim of this systematic study, trials wereincluded only if they studied the effects of MTon at leastone important clinical outcome, defined as measurementson the activity level in stroke patients and pain intensityin patients with CRPS and PLP, respectively.

8 Studies thatanalysed only cortical mechanisms of MT using measure-ments such as functional magnetic resonance imaging(fMRI) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) were also excluded if:(1) Only the theoretical background of MT was inves-tigated;(2) Only the (conference) abstract was strategy for identification of studiesStudies were identified by a computer-supported searchthrough August 2010 using the following databases:Cochrane Database of controlled trials, PubMed/MEDLINE,CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PEDro, RehabTrials andGerman databases such as DIMDI and Rehadat. Thesearch strategy that was used for databases such asPubMed and Cochrane served as the main protocol andwas then modified for searching other following keywords were used: imagery, mirror ,feedback/psychological, rehabilitation , therapy , stroke,amputation, phantom limb, complex regional pain syn-dromes and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. The detailedsearch strategies are available on request from the firstinvestigator ( ).

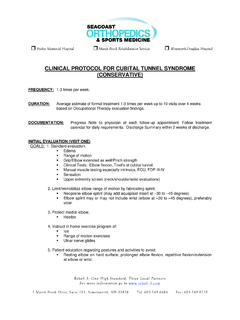

9 Additional methods used included screening of thereference lists of identified articles, search on the inves-tigators of identified studies and personal communicationwith experts in the field of collection and analysisAll sources were searched independently by two investiga-tors [ (researcher) andMarsha Jussen (librarian)] byapplying the stated selection criteria. Disagreement withregard to the study selection was resolved by consensus,and in the case of persisting disagreement a thirdinvestigator ( ) was of risk of bias and clinical aspectsTo assess the methodological quality of included RCTsand CCTs, we used the Amsterdam Maastricht Con-sensus List (AMCL) for Quality Assessment (Van Tulderet al., 2003) coupled with four additional items on quality2 International Journal of rehabilitation Research2011, Vol 34 No 1 Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is 1 Objective:Assessment of clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation afterstroke, complex regional pain syndrome and phantom limb painStudy selection:Randomized controlled trials as well as class II, III and IV studies in English, German, French and Dutch through August 2010 Adult patients suffering from stroke, phantom limb pain or complex regional pain syndrome mirror therapy using any mirror device and any task Outcome on at least one important clinical measureTwo investigators performed thesearch independently Data sources:Computer-supported search through August 2010 Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) PubMed/MEDLINE CINAHL Embase PsycINFO Rehadat Rehab trials Citations and author tracking.

10 Outcome: 791 Excluded: 760 articlesMain reasons: Duplicate identifications Study purposes other than clinical effects of mirror therapyIncluded class I articles: Six randomized controlled trials Four crossover studies: first part of study analysed, before crossover Included class IV articles:Seven patient series Four single-case studies Outcome: 11 articles Outcome: 10 articles Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias of selected articles using the Amsterdam Maastricht Consensus List and described study characteristics Risk of bias assessment:Twelve internal validity items: Amsterdam Maastricht Consensus List + four extra topics (Table 2) General conclusions, feasibility, essential additional or contradictory information on clinical aspects (Table 4) Included class II & III studies: noneReports retrieved for detailed evaluation (n=31)Excluded: 10 articles Main reasons: Only one treatment (n=4) Insufficient data (n=3)Study characteristics:Study design/population Interventions/tasks Results/outcomes (Table 3) Two independent investigators selected articles on title and abstract Overview of study selection and risk of bias aspects of mirror therapyRothgangelet Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.