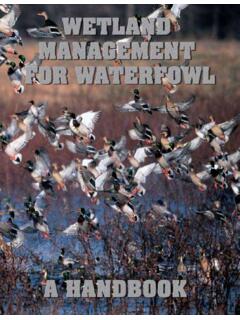

Transcription of Wetland Management For Waterfowl Handbook

1 Wetland Management FOR. Waterfowl Handbook . Mississippi River Trust Natural Resources Conservation Service United States Fish and Wildlife Service 2007. Edited and Compiled by Kevin D. Nelms, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Mississippi With Assistance From Brian Ballinger, Mississippi River Trust Alyene Boyles, Wildlife Mississippi Acknowledgements The following biologists made contributions to one or more parts of this publication: Brian Ballinger, Mississippi River Trust Leigh Fredrickson, Gaylord Laboratory, University of Missouri Brett Hunter, Fish and Wildlife Service, Louisiana Kevin D. Nelms, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Mississippi Jody Pagan, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Arkansas Pat Stinson, Fish and Wildlife Service, Mississippi Bob Strader, Fish and Wildlife Service, Mississippi Mark Tidwell, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Arkansas Photography Photographs courtesy of Russell Stevens and Chuck Coffey, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, Ardmore, Oklahoma; Jody Pagan, NRCS, Arkansas; Victor Ramey and Anne Murray, Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, University of Florida; James Manhart, Department of Biology, Texas A&M University; Robert Kowal, Kenneth Sytsma, and Michael Clayton, Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

2 Dennis Woodland, Biology Department, Andrews University; Robert H. Mohlenbrock, Patrick J. Alexander, Ted Bodner, Thomas G. Barnes, Larry Allain, Steve Hurst, Clarence A. Rechenthin, Jennifer Anderson, G. A. Cooper and William S. Justice, USDA-NRCS PLANTS database; Chris Evans, River to River CWMA, ; Mary Ellen (Mel) Harte, ; John D. Byrd, Mississippi State University, ; Steve Dewey, Utah State University, ; Brian Ballinger, Mississippi River Trust, Kevin D. Nelms, NRCS, Mississippi; and Michael Kelly, Wild Exposures Some of the photographs can be found on the internet at: Graphic Artist: Katherine G. Boozer Cover photograph provided by Michael Kelly, Wild Exposures, Wetland Management . FOR Waterfowl . Handbook . TABLE OF CONTENTS. Wetland types common to the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley ..1. Duck-use Waterbird migration season overview.

3 4. Wetland Management Strategies for Food and Habitat Moist-soil Management for wildlife ..6. Management of seasonally flooded impoundments for wildlife ..8. Strategies for water level manipulations in moist-soil systems ..19. Preliminary considerations for manipulating Other Waterfowl Foods Flooded food plots for Managing agricultural foods for Aquatic invertebrates important for Waterfowl production ..40. Invertebrate response to Wetland Life History and Wetland Management for Wood Ducks Life history and habitat needs of the wood duck ..54. Design for a wood duck Managing beaver to benefit Common Moist-Soil Plants Identification Guide Vegetation control Plant food value for Waterfowl ..72. Common Wetland plants (in alphabetical order) ..73-127. Appendix Moist-soil data sheet ..128. ii Wetland Types Common to the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley Seasonally Flooded Bottomland Hardwoods Bottomland hardwood wetlands are forested wetlands comprised of trees, shrubs, broadleaf herbaceous plants, and grasses that withstand flooding of various depths, duration, and times.

4 This is the predominant Wetland type in the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley (LMAV). When selecting tree species for planting, susceptibility of flooding and flood tolerance of species should be considered. Species that are tolerant of flooding will do well on elevated sites, but species intolerant to prolonged flooding will not do well on flood prone sites. If water control is possible on bottomland hardwood sites then it is called a greentree reservoir. Greentree reservoirs should only be flooded during dormancy, usually December 1 to March 15 in Mississippi. Early fall flooding can be more detrimental than late spring flooding. When managing greentrees, flooding and draining at the same time annually should be avoided. Water depth, duration of flooding, and flood timing should be changed each year. The reservoir should be left dry 1 in 4 years.

5 Improper flooding will result in tree stress and over time will kill desirable oaks and favor flood tolerant trees such as tupelo and cypress. Swollen and cracked trunks at water level, acorn crop failure, dead branches, and yellowish leaves are signs of tree stress and improper flooding. Moist-Soil Wetlands Moist-soil wetlands historically occurred where openings existed in bottomland hardwoods. Forest openings were often caused by high winds, catastrophic floods, beavers, fires, etc. Man- made impoundments are commonly managed as moist-soil wetlands. Moist-soil areas are typified by seed producing annuals such as smartweeds, wild millets, panicums, and sprangletop. Planting moist-soil areas is not necessary because native plant seeds are abundant in frequently flooded soils. Over 2,500 pounds per acre of seed can be produced in a properly managed moist- soil area.

6 Over time, plant succession will favor perennials and moist-soil areas will need to be disturbed. If more than one moist-soil area is being managed, it is best to stagger draining and flooding between units. This will increase plant diversity, prolong habitat availability, and increase wildlife benefits. Of 156 species of birds that use moist-soil, 131 prefer water depths 10 inches or less. Once again, varying depth, duration, and timing will provide the best results. Emergent Marshes Emergent marshes are generally 6 to 3' deep and contain vegetation rooted in soil that emerges above the water surface. Emergent plants include cattail, bulrush, spikerush, and sedges. These marshes are valuable as nesting and brood rearing habitat for resident wading birds. They also provide feeding, resting, and roosting habitat for migratory shorebirds and Waterfowl .

7 Emergent marshes are often managed in rotation with moist-soil areas. Maximum use of emergent marshes takes place when plant cover reaches 50 percent leaving 50. percent open water; this is called a hemimarsh. As marsh succession occurs, a marsh will move from open marsh to hemimarsh to predominately emergent cover. Emergent marsh succession 1. should be manipulated when invading woody plant stems are 2-3 inches in diameter. Disturbance is best accomplished by bushhogging and heavy disking. This will set succession back to the grass stage. This area can then be managed for moist-soil while another area is allowed to become emergent marsh. Water levels of emergent marshes can be drawn down in late summer and early fall to provide mudflats and shallow water for migrating shorebirds and teal. Shrub/Scrub Swamps Shrub/scrub swamps usually contain 6 to 24 of water during the growing season.

8 They are typified by willows, buttonbush, other woody species, and perennial herbaceous vegetation. In the LMAV, shrub/scrub swamps are often transitional between emergent wetlands and forested wetlands. Decaying leaves provide substrate for invertebrates which in turn provides food for waterbirds, fish, amphibians, and other Wetland wildlife. Studies have found over 25 pounds of invertebrates in an acre of flooded willows. Buttonbush seeds are often fed upon by wood ducks and mallards. However, the primary value of shrub/scrub is not food, it is thermal roosting cover for Waterfowl . On cold nights the low, thick vegetation helps retain heat. Microtopography/Depressions Historically, flooding in the LMAV resulted in shallow ridge/swale topography and isolated depressional areas. This is often referred to as microtopography.

9 Microtopography is important because it can provide valuable habitat for amphibians and feeding waterbirds. When creating microtopography, the goal is to create as much variation in depth, duration, and timing of flooding as possible. This can be accomplished by digging isolated depressions, digging depressions within other Wetland types, creative borrowing when constructing dikes, and by diking small suitable areas. Depressional wetlands found at high enough elevations to escape seasonal flooding are often called fishless ponds. These areas are valuable for amphibians since no fish or bullfrog tadpoles are present to feed on eggs or young. Water budgets for the Mississippi Delta have shown 3' depressions will maintain some water 9 out of 10 years. Deep Open Water Deep, open water is generally 3' or more deep and is usually a river, slough, brake, bayou, or oxbow lake.

10 These wetlands are valuable as fisheries and also provide resting and roosting cover for waterbirds. Deep, open water is generally not limiting but can provide valuable habitat in dry years. Wetland Complexes A variety of Wetland types located in close proximity will ensure that each Wetland species can meet its physiological requirements at each stage of its life. Most managed tracts are not large enough to provide all the previously mentioned Wetland types. However, different Wetland types should be provided and steps should be taken to provide Wetland types that are not available within adjacent areas. Studies indicate that a mallard must have all the resources needed for survival within a 12-mile radius. A good goal when planning is to provide bottomland forest, moist-soil wetlands, emergent marsh, shrub/scrub swamps, microtopography, and flooded cropland all within a 12-mile radius.